Back in my college days, I would always treasure my small reunions with high school friends during break. In these get-togethers, rowdy college stories were the commodity amongst my friend group and approving laughter was the currency to be exchanged. But storytime was always anxiety-inducing for me; even with my own wacky and gonzo adventures and experiences from being thrown in a new setting with colorful characters, I always felt that I could never do these stories justice with my own lack of oratory skills. When I played the Where the Water Tastes Like Wine port for Nintendo Switch, I kept thinking back to my trepidation about storytelling during that time in my life.

In this adventure game by Dim Bulb Games and Serenity Forge, stories are literally the commodity that the player seeks out to collect and eventually expend. While I admire the concept of the game, which absolutely succeeds in artfully depicting a Great Depression-era America, I had difficultly reconciling with how stories in Where the Water Tastes Like Wine are used as resources.

My realization in those college days was that a “sequence of events” and a “story” are different units—an event can be turned into different types of stories, depending on who is telling it and how they tell it. Stories are versatile and modular, and even with the successes of Where the Water Tastes Like Wine in creating an atmosphere, I lamented by how rigid storytelling was in this experience.

For those unfamiliar with the game’s premise from its original 2018 release, Where the Water Tastes Like Wine has the player as an anonymous traveler, who loses a game of cards against a wolfman and is bound to travel across the entire United States of America from East to West to collect stories. What plays out is what one could call a “walking simulator,” as the player controls a skeleton holding a bindle traveling on foot, with some opportunities for hitchhiking and train rides.

The game environment emphasizes the open fields, the hills, the mountains, the railroads, and the occasional industrialized city—images of Americana and the culmination of manifest destiny. Original folk tunes with full lyrics blare in the background, and the player can make their character whistle to the tunes to pace faster. Players will stop by houses and other indicated spots in the environment, witnessing events or participating in bizarre incidents written by a number of authors in the games industry. The prose carries a feeling of grit, matched with the narrator’s gruff recital.

I had particularly been looking forward to playing this game specifically on Nintendo Switch. In my head, I had built up the idea that Where the Water Tastes Like Wine on a portable console could be akin to reading a short story collection book, something that I can hold while cozied up in bed. While the atmosphere and prose drew me in and briefly led to me that this idea of mine would come to fruition, this Switch port had one ultimate downfall for me: the text was much too small. In portable mode, these stories were uncomfortable for me to read and would lead to actual headaches, and I was shocked that this port didn’t keep the Switch’s size in mind. It’s a simple flaw, and not the only game that suffers this issue on Switch. But it is an issue that snowballed, as my slight frustration with the game’s mechanics exacerbated as I delved deeper into the “storytelling portions” of the game.

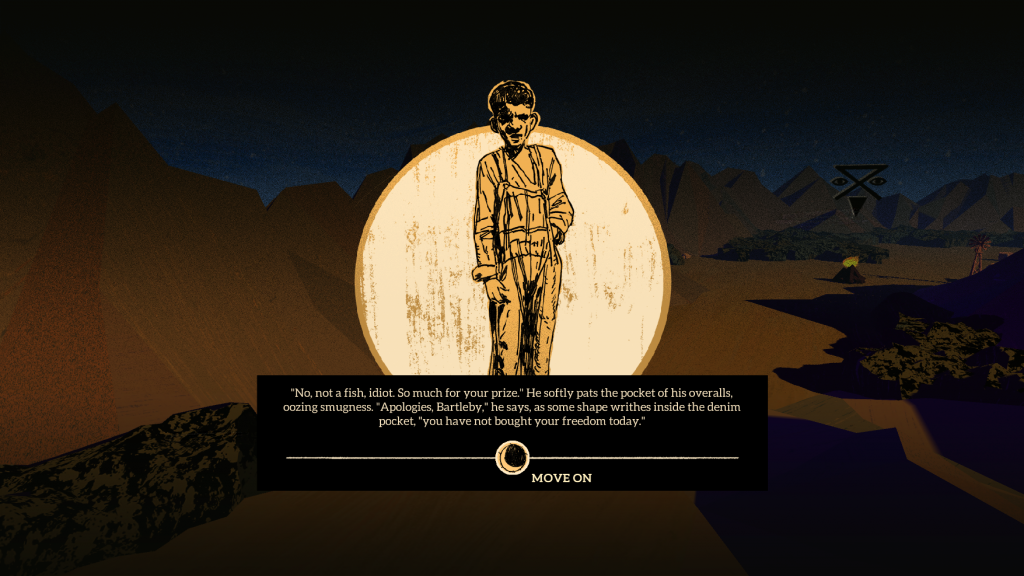

After amassing a number of anecdotes and strange tales, players will eventually encounter named characters on their journey; they are vagrants, weary travelers looking for rest and solace. Their source of solace turns out to be stories, and they’ll request that you tell them a specific type of story. Perhaps they will want to hear about topics like family or love, or they may seek a specific mood or emotion from your stories, such as sadness or joy. Regardless, they’ll show approval and satisfaction to your telling of the story, and in return, they’ll open up and offer you their own personal life stories and recollections.

The story that the player chooses will be picked out of a wheel, which divides up the stories they’ve amassed into a number of tarot card-like thematic categories. They’ll be reminded of what these stories are about from a one-line descriptor, although depending on their memory and how often they’re on the game, the player might not be able to recall what the heart of the story was (at least, this was my own experience). Your fellow traveler may appreciate the story or not, and the player will be given chances to give a “correct story.”

This is where Where the Water Tastes Like Wine begins to break for me. The player doesn’t necessarily get to see or listen to their character retell this story and is simply told that your character recites it. Storytelling is a complicated art form, one where cadence and disposition can make all the difference. Perhaps there is a story in the game that could be twisted or tweaked so that while the events may not be what your campfire companion is exactly looking for, it could be told in a way that fits the mood they are seeking. Stories are malleable and shift based on who is telling them, but to turn them into objects and to shift storytelling into something transactional felt contradictory.

It is a difficult balance to play—how does one exactly turn something as organic and freeform as storytelling into an interactive video game, as a product? I found myself running into the same frustrations that stopped me from playing games like L.A. Noire, which I felt was less about figuring out how to handle situations on your own but instead choosing the one strict option that the game wants you to choose. I felt that my logic was constrained, and I didn’t have the freedom to think as myself in sharing these stories and was cornered into figuring out what the designers had in mind to move forward.

There is no shortage of meta-fiction that tackles storytelling as a concept: the classic example is, of course, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, which explores how different people can recall an event in ways that slant their own prejudices and agendas. There’s a reason why the “Rashomon effect” is a real phenomenon, as different perspectives will view and retell the same sequence based on the way their brains take in pieces of information. And then there is something like Tim Burton’s adaptation of Big Fish, which has an ailing father with a penchant for telling his life story in a tall manner at the heart of the film.

Where the Water Tastes Like Wine is a beautiful and ambitious video game, but it feels hamstrung by the requirements of the medium. To have something as organic, animated, and unpredictable as storytelling into something coded and programmed would be a difficult feat to accomplish, and I’m happy that Where the Water Tastes Like Wine exists as a starting point, at the very least.

For now, at least we can experience the joys of our very own game of storytelling amongst friends and drinks.

The post Where the Water Tastes Like Wine Turns Organic Storytelling into Something Artificial by Chris Compendio appeared first on DualShockers.